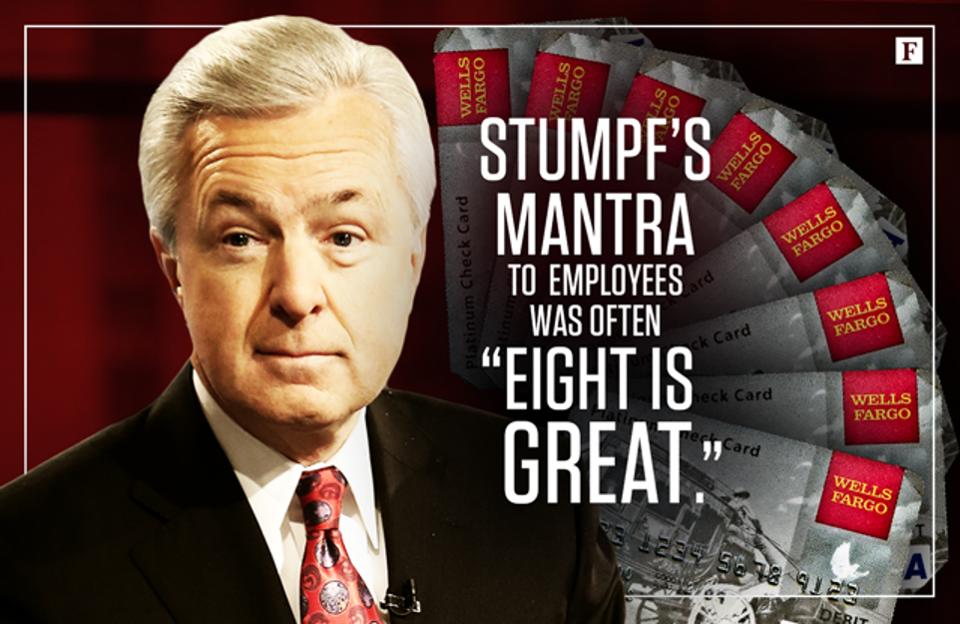

“Aim for Eight”

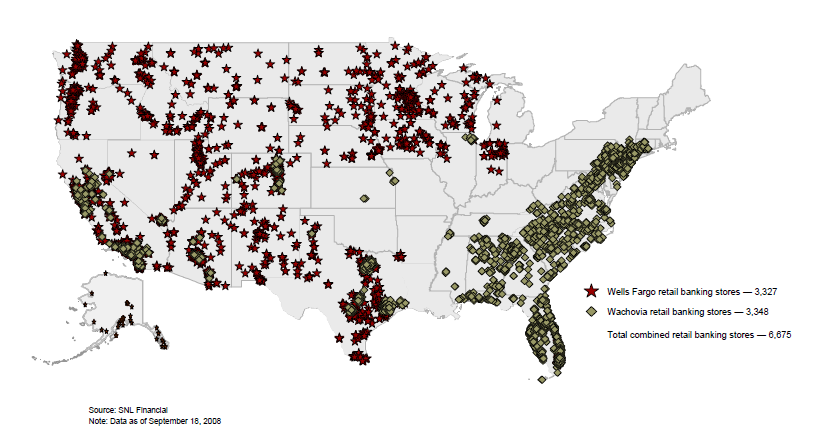

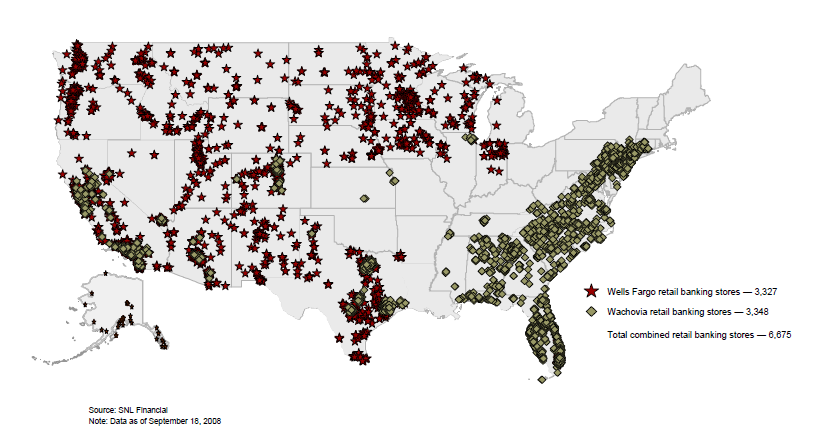

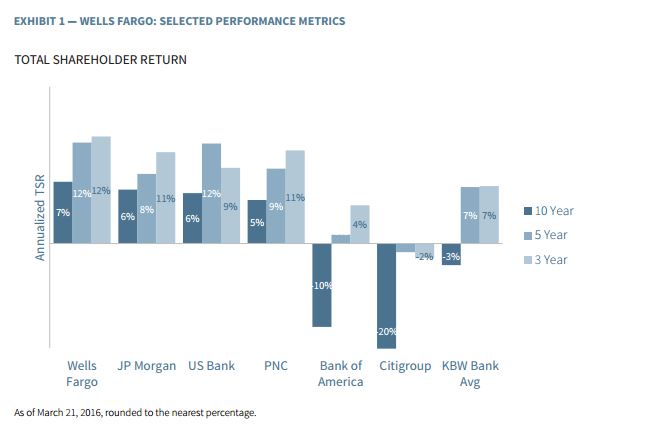

In summer of 2010, John Stumpf, Wells Fargo CEO, marched with his management team in front of an auditorium full of analysts to showcase Wells Fargo successes and strategies at bi-annual investor day. Spirits were high and optimism was abound. Wells emerged from ’08 financial crisis better than any other major bank in the US and with the prized Wachovia acquisition as a bounty. Carrie Tolstedt, then the Head of Community Banking at Wells, exuded confidence as she explained how her division “wants to satisfy all our customers’ financial needs and help them succeed financially.” “We’re creating one retail banking operating system to serve our customers coast-to-coast.”

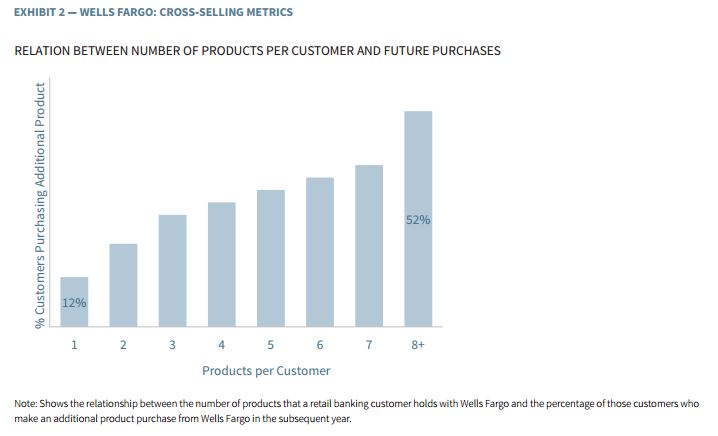

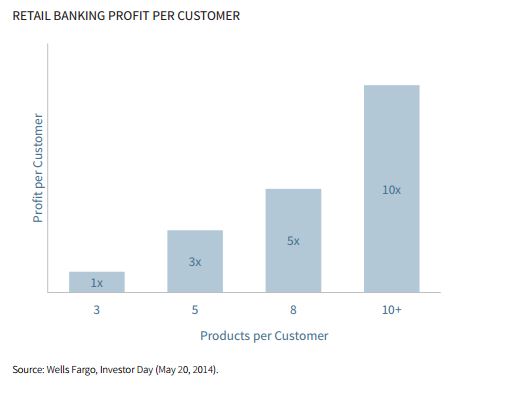

2009 Wells annual report reported a running score, to 2 decimal points, on the number of products Wells customers were sold. “Legacy Wells Fargo retail bank households have an average of 5.95 products with us; legacy Wachovia, 4.65. We want to get to eight.”

Why so much focus on sales of products? Wells management obsession with products sales harkens back to Stumpf’s days in Norwest Bank in Texas (before Norwest acquired Wells Fargo and rebranded new entity Wells Fargo). Stumpf was a Head of Community banking at Norwest as the bank set an ambitious goal to have average Norwest banking household have eight products with the bank. In Stumpf’s own words “Many analysts, focused only on the next quarter, yawned. That year, we averaged nearly four products per retail banking household. The next year, at the merger of Norwest and Wells Fargo, it was 3.2.”

In 2010 annual report, Stumpf celebrated Cross-sell milestone at Community Banking . We’ve been called, true or not, the “king of cross-sell.” To succeed at it, you have to do a thousand things right. It requires long-term persistence, significant investment in systems and training, proper team member incentives and recognition, taking the time to understand your customers’ financial objectives, then offering them products and solutions to satisfy their needs so they can succeed financially.

This year, we crossed a major cross-sell threshold. Our banking households in the western U.S. now have an average of 6.14 products with us. For our retail households in the east, it’s 5.11 products and growing. Across all 39 of our Community Banking states and the District of Columbia, we now average 5.70 products per banking household (5.47 a year ago). One of every four of our banking households already has eight or more products with us. Four of every ten have six or more. Even when we get to eight, we’re only halfway home. The average banking household has about 16. I’m often asked why we set a cross-sell goal of eight. The answer is, it rhymed with “great.” Perhaps our new cheer should be: “Let’s go again, for ten!”

Number of products per average customer

2010

2009

Stumpf’s rise to the top came the old fashioned way – he earned it.

Stumpf was a talented banker and his rise to the top came the old fashioned way – he earned it. Stumpf grew up as one of 11 children on a dairy and poultry farm.His father was a dairy farmer. His father is of German descent and his mother of Polish descent. He was raised as a Catholic. Stumpf shared a bedroom with his brothers until he was married.

Starting from the bottom and moving his way up, Stumpf got his start in banking as a repo man at First Bank in St Paul, Minnesota. “You would track [the overdue car] down, call the tow truck and just as the car started to lift off the ground, out of the bar would walk a giant of a guy with two six-packs of confidence in him and he wants to know what you are doing with his car. Now that is exciting! You learned the power of persuasion,” ”When you collect bad loans…. you sure learn a lot about making good ones”. You also learn a lot about the power of persuasion, persistence and desperation.

Starting from the bottom and moving his way up, Stumpf got his start in banking as a repo man at First Bank in St Paul, Minnesota. “You would track [the overdue car] down, call the tow truck and just as the car started to lift off the ground, out of the bar would walk a giant of a guy with two six-packs of confidence in him and he wants to know what you are doing with his car. Now that is exciting! You learned the power of persuasion,” ”When you collect bad loans…. you sure learn a lot about making good ones”. You also learn a lot about the power of persuasion, persistence and desperation.

Six years later, he joined Northwestern National Bank which became Norwest and quickly rose up the ranks to become the chief credit officer for Minneapolis. In 1998 Norwest was scooped up by Wells Fargo in 1998. As the company grew, so did Stumpf’s reputation and responsibilities. In 2002, Wells Fargo put him in charge of community banking. In December 2008, he led one of the largest mergers in history with the purchase of Wachovia.

Wells Fargo culture in action

His big move: outmaneuvering Citigroup’s Vikram Pandit to acquire North Carolina’s troubled Wachovia bank at the height of the meltdown, in early October 2008. It’s a textbook case of Wells Fargo’s culture in action. “We got a call about Wachovia, and we pulled all-nighters that whole weekend, but by Sunday night, we had to ask for more time,” says Stumpf. We simply could not complete our analysis, even though we loved Wachovia and its people and its businesses. One of our corporate disciplines is you don’t buy things you don’t understand.

Stumpf and his San Francisco team kept tearing apart the financials: “We didn’t put our pencils down.” By Thursday they had a grasp on the business and were convinced that it could meet their internal criteria: adding to earnings per share no later than the third year after purchase and creating an internal rate of return of at least 15%. That evening Wells came over the top with a successful $15 billion offer for the whole company, without help from Uncle Sam and ultimately without the severe pain that BofA felt after it swallowed Countrywide.

The methodical Wachovia integration, which doubled Wells Fargo’s size, was fully completed this past November. Using Wells Fargo “buddy bankers” to infuse culture and best practices, every one of Wachovia’s 4,000-plus branches is now a Wells Fargo store. Following another precept from Stumpf’s vest pocket book, “retain and retrain,” only 1.5% of its workforce was eliminated.

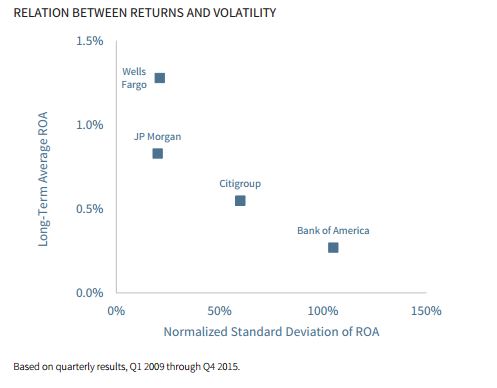

Attitude to Risk and Customer Service

Wells ability to acquire Wachovia in the midst of deepest financial crisis since Great Depression had been enabled by staying rational and reining in risk loans during the bubble years when bankers were falling over each to lend more to progressively less creditworthy clientele. From 2003 to 2006 Wells Fargo pulled away from the riskiest subprime mortgages, and its market share fell. “We didn’t originate an option arm loan in our entire career here,” says Mike Heid, president of Wells Fargo Home Mortgage. “Inside the organization there was a lot of encouragement to take the long-term view even though the outside world was saying that we just didn’t get it.”

Similarly, back in 2006 Wells’ chief risk officer, Michael Loughlin, clashed with the head of Wells Fargo’s $26 billion auto-lending portfolio, who he felt tolerated junky underwriting standards. Eventually, Loughlin took his case to the full board of directors; the entire operation, based in Des Moines, was shut down. “There’s only three jobs at Wells Fargo: taking care of existing customers, getting new customers and managing the risk of those two things,” adds Loughlin. “Nowhere in there am I talking about profitability or market share.”

Decentralized organization, empowered divisions

Stump management philosophy centered on empowerment. “I never set out to be CEO. I always set out to be a good team member, a good colleague. “I think star performers are my favorite to manage and lead. Star performers are critical to any organization and the key is how can you capture their heart-share and their mind-share when they’re on this fast track.” “I think great bosses hire great people. ‘A’ people hire ‘A’ people but ‘B’ people hire ‘C’ people; they’re worried they might be shown up… they’re concerned that that person might make them look bad.”

“I’d rather trust someone and be disappointed than not trust someone and be disappointed. People need to know where the guard rails are. I want people to live within those guardrails but also make some mistakes. Every success that I know of was preceded by a number of mistakes. That’s how humans learn.”

“We believe in plural pronouns, our, us, we always look to have a long term relationship with our team members. Do people leave, I believe people leave their manager, they don’t leave their companies.”

“Risk taking, especially personal risk taking, is something that is part of the culture of the company, Where do you find that magic space, that secret sauce, between adequate risk taking and not too much risk taking.’

“So in our company, we try not to make decisions by committee, we try to make them individually. We want peoples names to be on decision and with decision happen poorly or something doesn’t go right, we actually celebrate that, we share that information so we all learn from that.”

Stumpf offered a career advised: “Work for a company that you love, that shares your values. Work for a boss who cares about you, really cares about you. And then invest in yourself – you’re the best investment you can make.” His expression made clear that he wanted to be that boss who cares.

Carrier Tolstedt – Stumpf’s “principled banker” to the end

The way Tolstedt reportedly told the story, she became captivated by the power of community banking as a child in a small Nebraska town. Tolstedt’s father ran a small local bakery and they would occasionaly visit their local bank. “The bank staff were so nice. They knew my dad by name,” she told American Banker in 2010. “They treated him with respect.”

A graduate of the University of Nebraska, Tolstedt joined Norwest in 1986, rose through the ranks to oversee branches in Omaha and subsequently nationwide. One of her biggest goals, and one directly tied to Tolstedt compensation, was to raise the “cross-sell ratio,” a number of financial products were held on average by customers.

Tolstedt was committed to “Eight is Great” motto and created a formidable sales organization within the community banking. Bank tellers and customer service res were encouraged to use their own initiatve to sell customers more products ranging from checking accounts, credit cards, mortages, insurances and various types of loans. Wells annual report regularly featured stories on the front cover of how Wells staff helped customers who in turn happily signed up to another Wells product. Tolstedt enthusiastically embraced the concept of making 6,000 Wells branches the laboratories for experimenting in new sales techniques.

Experimentation worked wonders. Staff who came up with ingenious was to sell more were hailed as heroes. Sales organization naturally works its best when front-line people with more intimate knowledge of customer needs and circumstances are empowered to take the initiative. All that is required to unlock the sales potential is a strong incentive system to drive the behaviors and outcomes in a way that encourages staff to offer customers more products.

Incentives and the institutional imperative worked like a charm. 2009 Annual report, page 11, talks about Hanh Nguyen, a teller in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Nguyen noticed something as she was handing her customer her banking statement. She asked a simple question: “How much are you paying in auto insurance?” Nguyen asked if she had time right now to see if Wells Fargo could offer a better deal. Together, they called a Wells Fargo Insurance agent. An hour later, the customer saved $400 a year in premiums. Jamie Berthiaume, Team Member, Colorado Springs, enthused that if we see a home equity loan isn’t the right fi t, we’ll connect the customer with other Wells Fargo experts for personal loans, or mortgages or other services. We’re a gateway into Wells Fargo.”

Stumpf and Tolstedt worked out the magic formula to win in community banking – cross-selling. Wells Fargo operated on a decentralized model inherited from Norwest. Since at least the time of the 1998 merger between the two banks, a commonplace phrase within the company was “run it like you own it.” This guiding principle encapsulated the freedom Wells Fargo’s lines of business traditionally had not only to determine their own business activities, but also to independently exercise staff and control functions, such as Risk and Human Resources.

Carrie Tolstedt, who was promoted to be the head of regional banking in the Community Bank in 2002 and the head of the Community Bank in 2007, was one of those leaders. And while Wells Fargo’s decentralized model naturally afforded Tolstedt significant independence in that position, her record of success and strong financial performance enabled Tolstedt to maintain and enhance her authority.

Stumpf, for whom Tolstedt worked, was full of praise for her. “When you mix that intellect and attention to detail with this wonderful human — a person who can empathize and deal with a team — that’s where the magic happens,” he told U.S. Banker in 2007.

Following Wachovia acquisition, Wells doubled number of branches, thus increasing the opportunities for cross-selling. Wells was winning in the market place. Even as reports of questionable sales practices surfaced, Stumpf inherent instinct to empower Tolstedt, “A” player, meant that issues were largely attributed to the actions of “employees who violated Wells Fargo’s rules without analyzing what caused or motivated them to do so”. Effect was confused with cause.

Inside Wells Fargo & Co., some executives called Carrie Tolstedt “the watchmaker” for her obsessive attention to detail in running the firm’s sprawling retail-banking operation. Could questionable practices have really escaped her notice as the executive responsible for the bank’s 6,000 branches across the U.S.

Commenting on Tolstedt’s retirement, Stumpf called her a “principled” banker and a “dear friend.” Wells paid her $9.5 million in 2015, quoting “strong cross-selling ratio” and her contribution towards “reinforcing a strong risk culture,” according to filed documents.

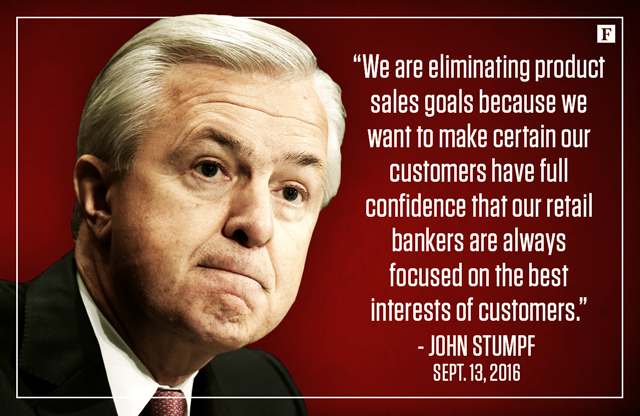

During Congress grilling in ’16 and before his resignation, Stumpf said he was “deeply sorry” the bank didn’t act sooner to stop the misconduct. As for firing Tolstedt, though, he said he never even considered it.

Vision, Values and The Art of Cross-Sell

“When I first became CEO, I got a call from another big bank CEO who said, ‘I’m coming through town. You guys are big in this cross-sell. I’ll buy you lunch. Tell me how you do it,’” recalls John Stumpf. “I told him, ‘I can’t eat that long and I can’t eat that much because it would take hours—days—weeks to talk about it.’” Stumpf was being polite.

In Vision and Values, Wells mission statement document, endoctrinated to its 270,00 strong workforce, company defines “’culture”’as knowing what you need to do when you get up in the morning without having to be told what to do. A good strategy perfectly executed will beat a great strategy poorly executed every time.” And famously: “The core of our vision and our strategy is “cross-selling.” … The more we give our customers what they need, the more we know about them. The more we know about their other financial needs, the easier it is for them to bring us more of their business. The more business they do with us, the better value they receive, the more loyal they are. At Wells Fargo, sales and service are inseparable. More sales do not always lead to better service, but better service almost always leads to more sales. Money is a commodity. We’re in the service business.”

Extract from Independent Directors of the Board of Wells Fargo & Company – Sales Practices Investigation Report:

“There was a growing conflict over time in the Community Bank between Wells Fargo’s Vision & Values and the Community Bank’s emphasis on sales goals. Aided by a culture of strong deference to management of the lines of business (embodied in the oft-repeated “run it like you own it” mantra), the Community Bank’s senior leaders distorted the sales model and performance management system, fostering an atmosphere that prompted low quality sales and improper and unethical behavior.”

The damning report

Board of directors commissioned an independent investigation into sales practices and made the report public. Below are direct quotes.

Sales model & unrealistic targets

Senior management in the Community Bank had a deep-seated adherence to its sales model. The model generally called for significant annual growth in the number of products, such as checking accounts, savings accounts and credit cards, sold each year. Even when challenged by their regional leaders, the senior leadership of the Community Bank failed to appreciate or accept that their sales goals were too high and becoming increasingly untenable. Over time, even as senior regional leaders challenged and criticized the increasingly unrealistic sales goals — arguing that they generated sales of products that customers neither needed nor used — the Community Bank’s senior management tolerated low quality accounts as a necessary by-product of a sales-driven organization.

Institutional imperative

In addition, keeping the sales model intact and sales growing meant that the Community Bank’s performance management system had to exert significant, and in some cases extreme, pressure on employees to meet or exceed their goals. Many employees felt that failing to meet sales goals could (and sometimes did) result in termination or career-hindering criticism by their supervisors. Employees who engaged in misconduct most frequently associated their behavior with sales pressure, rather than compensation incentives, although the latter contributed to problematic behavior by over-weighting sales as against customer service or other factors. Conversely, employees saw that the individuals most likely to be praised, rewarded and held out as models for success were high sales performers.

Role of Leadership

Wells Fargo’s decentralized organizational structure and the deference paid to the lines of business contributed to the persistence of this environment. Tolstedt and certain of her inner circle were insular and defensive and did not like to be challenged or hear negative information. Even senior leaders within the Community Bank were frequently afraid of or discouraged from airing contrary views. Tolstedt effectively challenged and resisted scrutiny both from within and outside the Community Bank. She and her group risk officer not only failed to escalate issues outside the Community Bank, but also worked to impede such escalation, including by keeping from the Board information regarding the number of employees terminated for sales practice violations. Although they likely did so to give themselves freedom to address these issues on their own terms, rather than to encourage improper behavior,1 the dire consequences and cost to Wells Fargo are the same.

The Blame Game

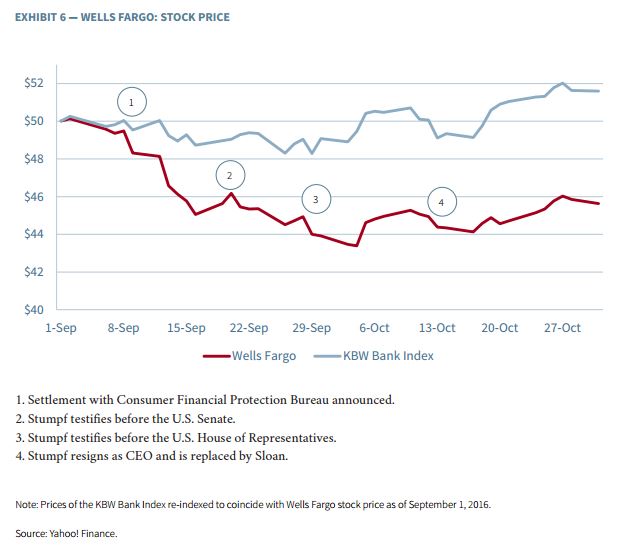

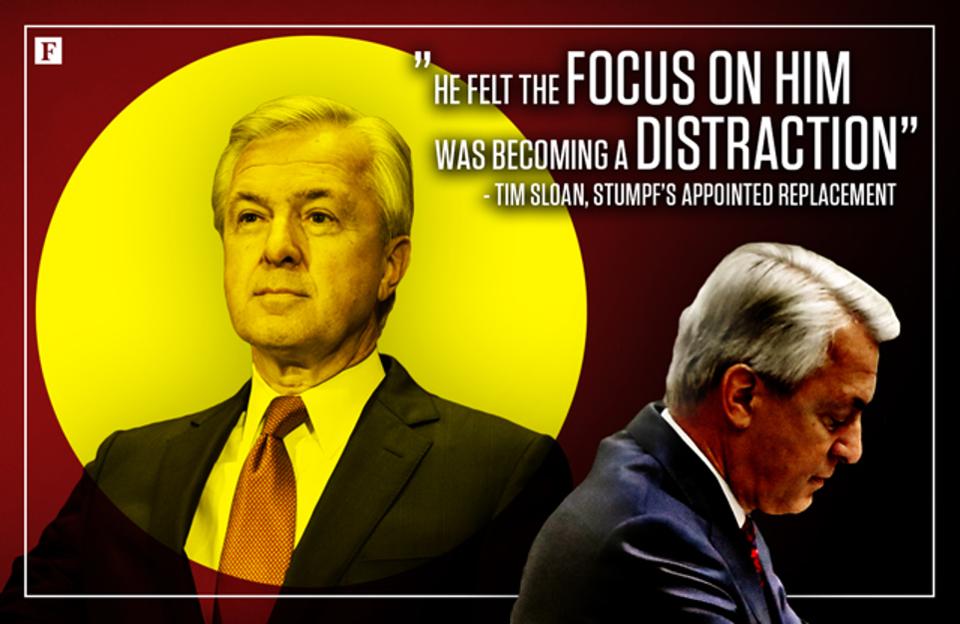

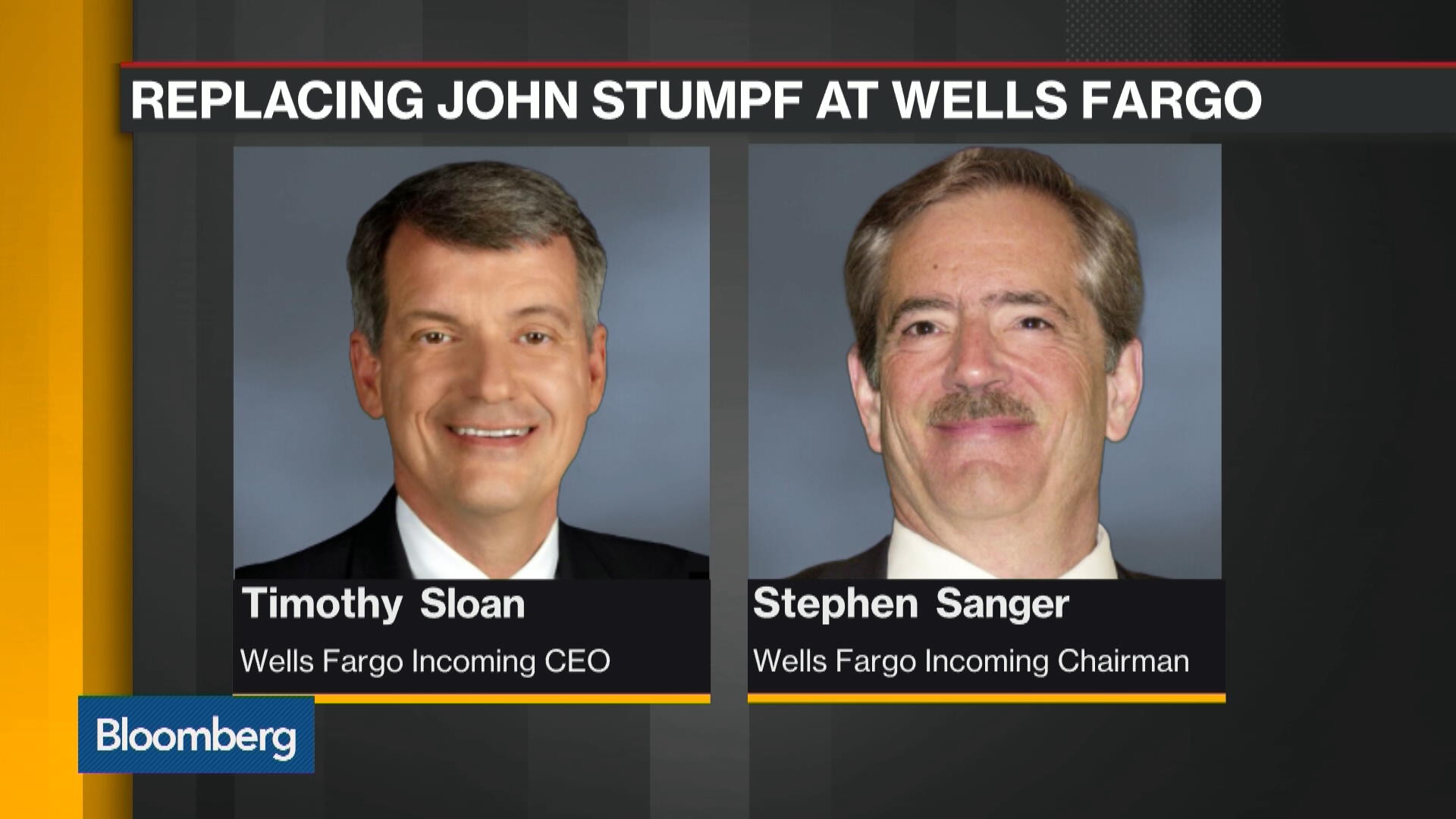

While responsibility most surely does not lie with John Stumpf alone, he rightfully acknowledged that he made significant mistakes and helped create the culture that resulted in sales practice abuses.

After decades of success, Stumpf was Wells Fargo’s principal proponent and champion of the decentralized business model and of cross-sell and the sales culture. His commitment to them colored his response when sales practice issues became more prominent in 2013 and subsequent years and led him to stand back and rely on the Community Bank to fix the problem, even in the face of growing indications that the situation was worsening and threatened substantial reputational harm to Wells Fargo. He was too late and too slow to call for inspection of or critical challenge to the basic business model.

Stumpf’s long-standing working relationship with Tolstedt influenced his judgment as well. Tolstedt reported to Stumpf until late 2015 and he admired her as a banker and for the contributions she made to the Community Bank over many years. At the same time, he was aware that many doubted that she remained the right person to lead the Community Bank in the face of sales practice revelations, including the Board’s lead independent director and the head of its Risk Committee. Stumpf nonetheless moved too slowly to address the management issue.

Even when senior executives came to recognize that sales practice issues within the Community Bank were a serious problem or were not being addressed timely and sufficiently, they relied on Tolstedt and her senior managers to carry out corrective actions. This culture of deference was particularly powerful in this instance since Tolstedt was respected for her historical success at the Community Bank, was perceived to have strong support from the CEO and was notoriously resistant to outside intervention and oversight.

John Stumpf - CEO

Carrier Tolstedt - Head of Community Banking

$mln

%

% of 2011-16 Compensation

$mln

%

% of 2011-16 Compensation

Historic Clawback

Following the release of the above-mentioned report detailing the findings of Wells board’s investigation into the problems, the board moved decisively to impose the highest clawback of bank executive compensation on record. Board decided to retroactively fire Tolstedt for cause, employing a harsh distinction rarely used in an industry and clawback $67mln of her compensation. Former CEO John Stumpf had to relinquish $69mln of his past comepensation.

While Tolstedt’s total clawbacks, at $67 million, are slightly less than the $69 million that Stumpf lost, once expressed as a percentage of the overall package, the board left little doubt around its views where the primary blame for the misconduct lies. Stumpf’s total pay from 2011-2016 was $286 million, according to executive compensation firm Equilar, meaning he will have forfeited 24 percent of his pay for that period since the scandal first emerged.

When Tolstedt resigned from Wells Fargo in 2016, she was walking away with $124.6 million in stock, options, and restricted Wells Fargo shares. After board’s intervention, that figure was cut in half.

3 significant mistakes

Warren Buffett, Wells biggest shareholder, is known for his folksy and insightful remarks on business affairs. When asked for his opinion, Buffett recounted 3 lessons.

Mistake 1: Organizations will have an incentive system. Wells’ system centered on cross-selling and number of products sold and that was incentivizing wrong behaviors. As Charlie Munger says, “I’ve been in the top 5% of my age cohort all my life in understanding the power of incentives, and all my life I’ve underestimated it. Never a year passes that I don’t get some surprise that pushes my limit a little farther.

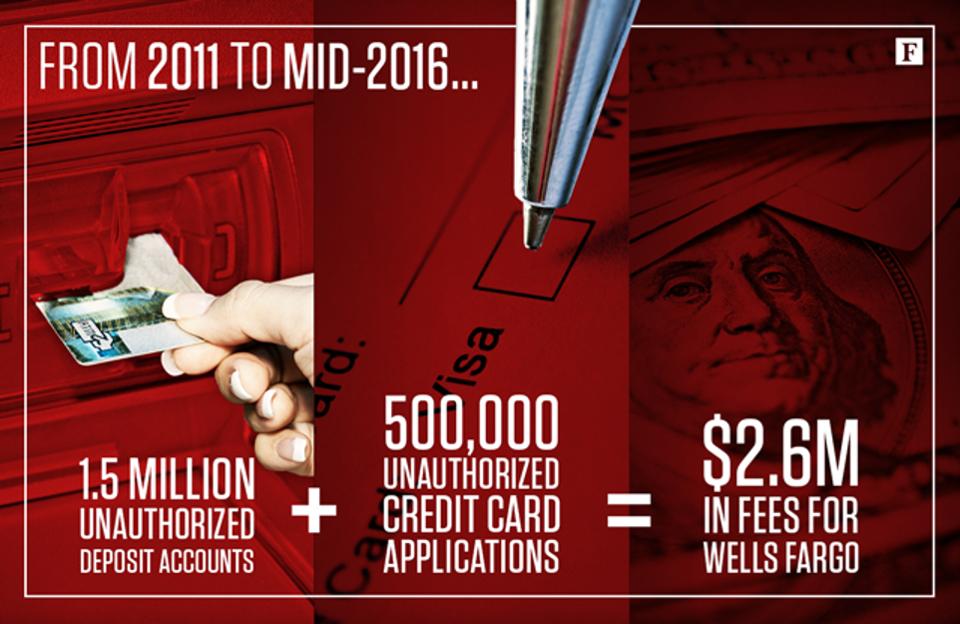

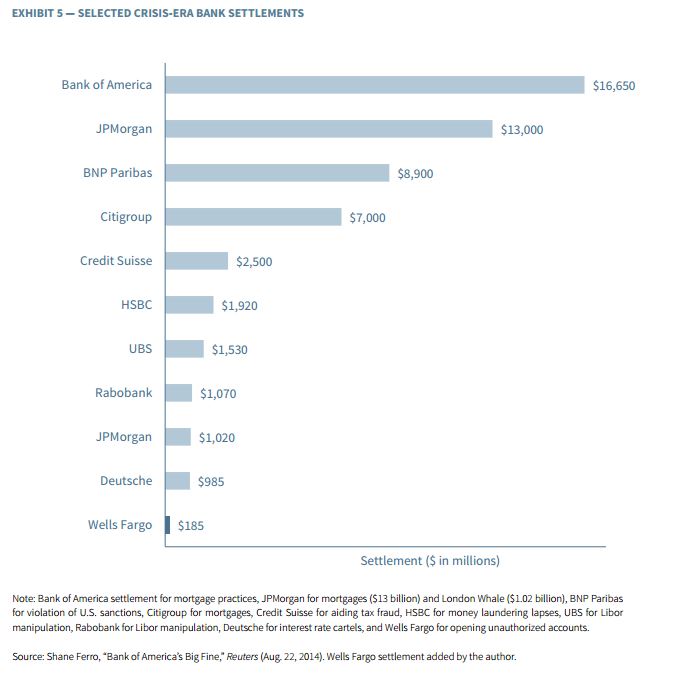

Mistake 2: Management totally underestimated of the impact of the problem. Bank was fined $185mln, which by recent standard is a modest amount. Management measured the seriousness of the problem by the dimensions of the fine. The size of the fine signaled less offensive practice.

Mistake 3: The most serious mistake in fact, was committed when CEO learnt about the wrong behaviors, he failed to act. “At some point, if there’s a major problem, the CEO will get wind of it,” he said. “And at that moment, that’s the key to everything.”

“It’s a great bank that made a terrible mistake,” Buffett told CNN’s Poppy Harlow in an interview on Friday. “It was a dumb incentive system, which when they found out it was dumb they didn’t do anything about it.”

Buffett was referring to the intense pressures on branch workers to hit certain sales quotas; Stumpf himself had been known to say, “eight is great.” Meaning: let’s aim for eight Wells Fargo products per household that’s a Wells Fargo customer.

Unfortunately, as became evident by the two million-plus bank and credit card accounts that were fraudulently opened, this sales pressure was too much to bear. Wells has since abandoned all sales quotas for its retail bank.

“It was a dumb incentive system, which when they found out it was dumb they didn’t do anything about it,” Buffett said Friday. He acknowledged that “incentives have terrific power” and that everyone uses them — even parents. But, he said, incentives can also produce bad behavior, which is what happened at Wells.

“Wells Fargo designed a system that produced bad behavior. When you find that out you gotta do something about it, and the big mistake was they didn’t do something about it,” he said.

1 Silver Lining

Despite the damage to Wells reputation, Buffett publicly opined that he doesn’t believe the underlying earning power of Wells franchise is impaired by the episode. So after all, Well is still a great bank even after making a terrible mistake.

0 Comments